We’ve been lucky enough to nab an exclusive extract from the brilliant new book, Playwriting: Structure, Character, How and What to Write, by internationally acclaimed playwright, Stephen Jeffreys. If you want an authoritative guide to playwriting from a true master of the craft, then you can get your hands on a copy, here.

In this extract, Jeffreys looks at the relationships between characters, and how strengthening these can drive your whole play forward.

You will probably have noticed from your own writing that certain characters come to life more immediately than others. The experience of writing a first draft is often one of sudden bursts of light illuminating stretches of relative darkness. More particularly, there is a tendency for certain characters to spark off each other so that when they are on stage together the dialogue flows and tension crackles. Conversely, some characters walk into the play and, like the guests who can put a dampener on any party, the whole thing falls flat. Nearly always this effect is reversible. It’s generally caused by the writer failing to consider in depth what a relationship between two characters has to offer. To some extent, writing successful plays is more related to writing strong relationships than writing strong characters (though Brecht might be an exception).

As soon as a character meets another character, a different aspect of their nature is revealed. We all play a variety of roles in our lives: we might within the space of a few hours appear as parent, child, spouse, worker, customer, carer, and so on. A successful constellation of characters will tease out a large number of different facets of the characters and provide the opportunity to explore these facets deeply. Edward Bond suggested that every character should meet every other character in the play. That obviously doesn’t apply to works of such epic sweep as Antony and Cleopatra, but it does apply to relatively small-scale plays.

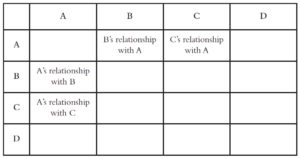

The best way to ensure that you are making the most of all the possible relationships in the play is to create a grid like this, where you consider each character’s perception of their relationship with the other characters:

When you have written the first draft, you might proceed by working carefully through the whole play and in each box summarising all the characters’ relationships with each other. I’ve deliberately left the ‘D’ boxes blank above, but when you come to fill them all in, I suspect that you’ll realise that, while about one-third of the relationships are very strongly realised, another third will be patchy, and the final third not well-achieved at all. If one of the characters seems especially weak after you’ve made the analysis, then a radical rethink of this character is required. Tinkering with small-scale ideas will not solve the problem. The character will need a substantial change of motivation or personality for them to contribute. However, if most of the characters seem to be operating successfully and there are only a few relationships which seem underachieved, it is likely that small adjustments here and there will take the play further forward. When faced with a weak relationship, ask yourself what the characters could possibly want from one another, or what they would especially find to like or dislike about each other. Sometimes the key lies in avoiding the obvious; for instance, my university professor, a reserved and conventional figure, was always drawn to the most anarchic and disreputable students. People who have very different outlooks can sometimes find surprising grounds for companionship, while people who show every signs of being compatible will often rub each other up the wrong way. You might wish to make two grids: one which summarises the relationships at the start of the play and then one which assesses how the characters feel about each other at the end.

You will find that your constellation of characters when taken as a totality constitutes the overall moral world of the play. A Jane Austen novel will contain a relatively narrow worldview since they are all drawn from the same class, while a Brecht play might allow for a wide range of divergent philosophies. The moral range on offer in a play or film impacts directly on our judgements of the characters. The Godfather is a good example of this: all the characters are terrible people. However, the Corleones are preferable to the other mafia groups because we see them taking care of their families and upholding traditional Italian values. Unlike Bruno Tattaglia, who is a pimp and deals drugs to children, the Corleones make some attempt to protect the innocent from their criminal activities. When compared with the other families, the Corleones seem like regular guys. If the constellation of characters consists entirely of appalling people, those who are slightly less appalling will stand out as examples of relative goodness. In a generally unsympathetic play, someone who offers someone else a cup of tea looks like a saint. Alternatively, in a play which otherwise evinces a relatively limited worldview, a moral challenge can be made by a character who comes from outside the prevailing group. In Osborne’s Look Back in Anger, the dominant group of young bohemians is challenged by the arrival of the Colonel in Act Two. In some plays, two conflicting worldviews are portrayed simultaneously: Timberlake Wertenbaker’s Our Country’s Good shows us the convict class and the officer class, for example. In a play like The Merchant of Venice, because the range of characters is greater, the clashes (between Christians and Jews, servants and masters, men and women) become more complex, and the moral world of the play more multifaceted.

This is an extract from Playwriting: Structure, Character, How and What to Write by Stephen Jeffreys, edited by Maeve McKeown, and out now, published by Nick Hern Books.

This is an extract from Playwriting: Structure, Character, How and What to Write by Stephen Jeffreys, edited by Maeve McKeown, and out now, published by Nick Hern Books.

Find out more and order your copy here